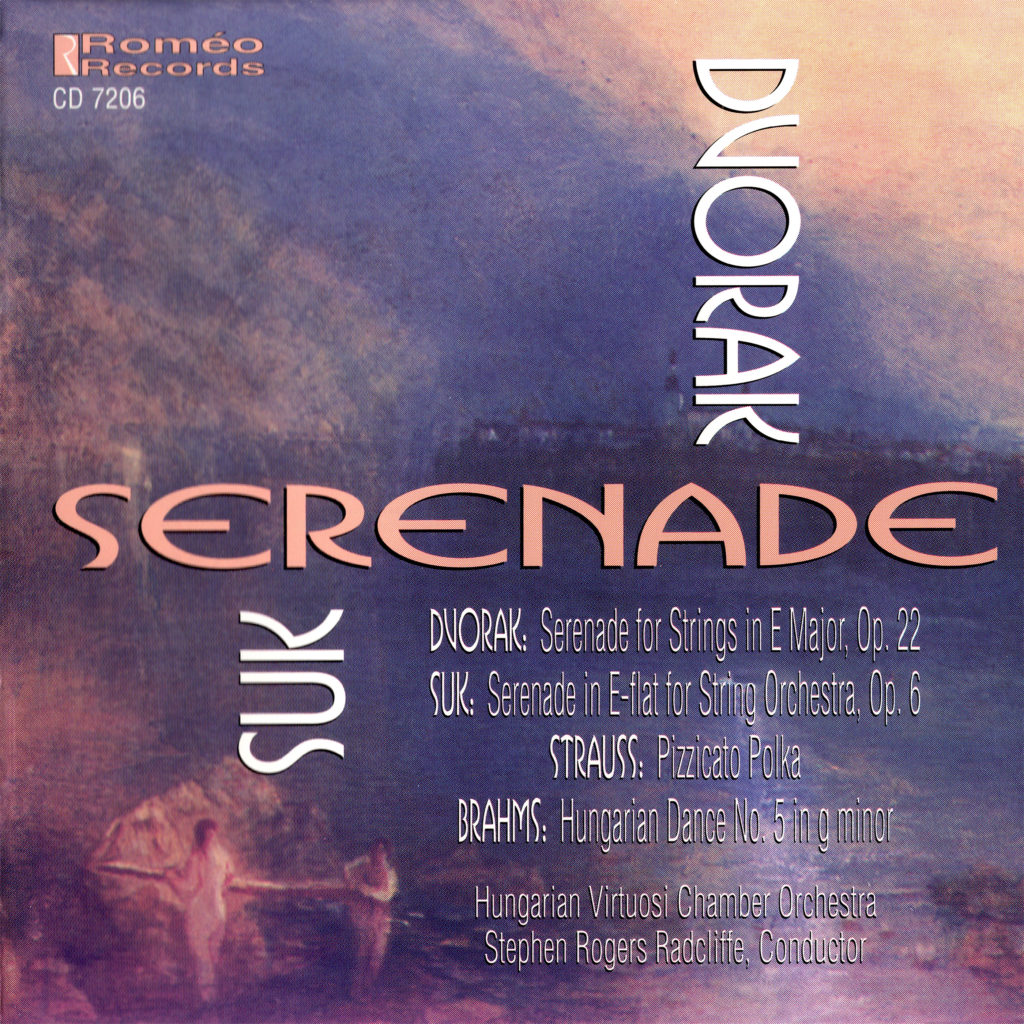

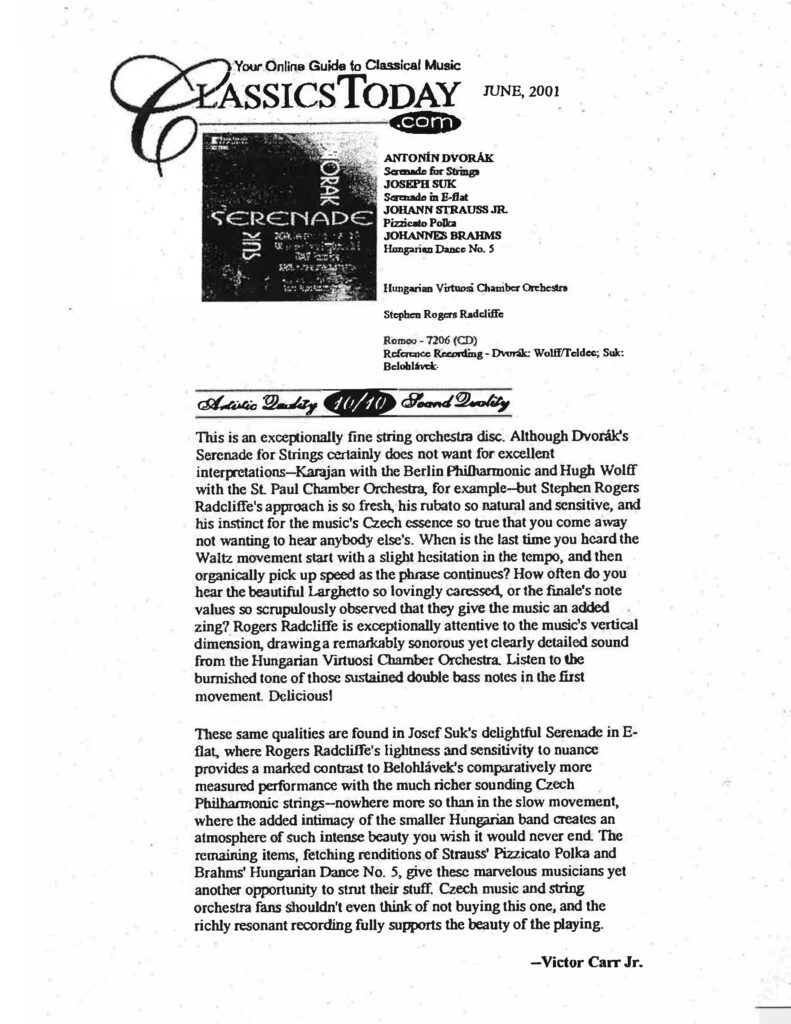

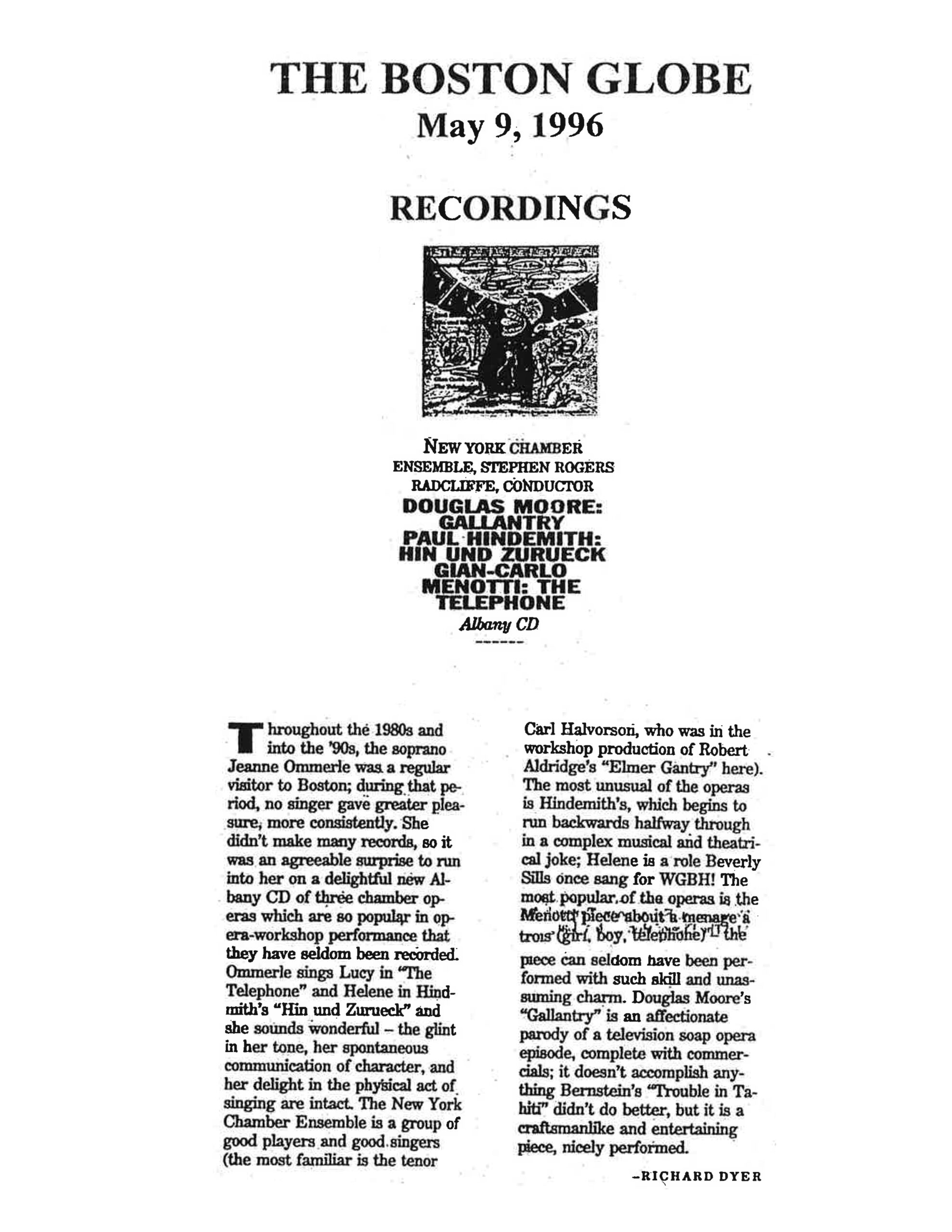

Press | Recording Review

September 2001

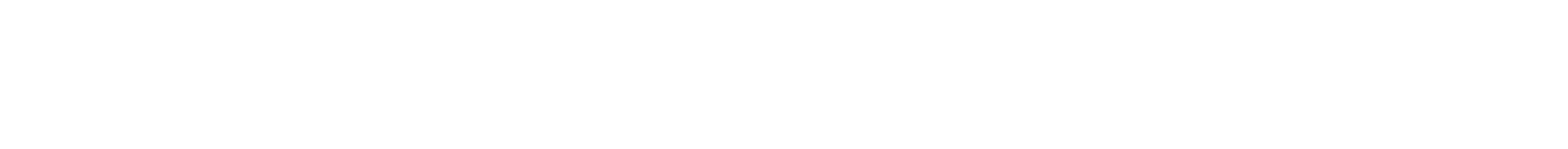

Brahms • Franck [N]

Brahms Serenade in D, Op 11 (nonet version, reconstr Boustead)

Franck Pièces brèves (arr Büsser)

The New York Chamber Ensemble / Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe

Roméo Records 7209 (55 minutes: DDD)

A fresh, lyrical account of Brahms’s Serenade in its near-to-original chamber version

By Donald Rosenberg

Brahms’s Serenade No 1 in D major, Op 11, is known largely in the orchestral guise the composer devised in 1859. But he conceived the piece first as a chamber work for flute, two clarinets, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and bass. The original 1858 version, in a reconstruction by Alan Boustead, is the chief fascination on this disc from the New York Chamber Ensemble under Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe. As Clara Schumann suggested to Brahms, the score claimed a symphonic character that seemed to cry out for more instruments. Even so, the chamber version places the music in intimate relief, pointing out the long-breathed lyricism and lilting personality of the pastoral material. Brahms even provided a hint in the orchestral version that he was fond of the smaller incarnation: the Menuetto I and II in the former are scored for flute, two clarinets, bassoon, first violins, violas and cellos. Boustead’s reconstruction may be speculative, but it honours Brahms’s sound world even as it embraces the music’s charm, poetry and moments when the sun slips behind the clouds.

The disc’s other novelties are three of Franck’s Pièces brèves, organ miniatures from the last year of the composer’s life orchestrated by Henri Büsser. They are delightful trifles beautifully cast for winds, brasses, strings and percussion.

The New York Chamber Ensemble, which made this recording in November 1992, brings ample polish and expressive depth to both scores. The Brahms, from a studio performance, is rendered fresh as motivated by Radcliffe’s judicious tempos and attention to detail and his players’ vibrant interweaving of lines.

![Gramophone September 2001 Brahms • Franck [N] Brahms Serenade in D, Op 11 (nonet version, reconstr Boustead) Franck Pièces brèves (arr Büsser) The New York Chamber Ensemble / Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe Roméo Records 7209 (55 minutes: DDD) A fresh, lyrical account of Brahms’s Serenade in its near-to-original chamber version Brahms’s Serenade No 1 in D major, Op 11, is known largely in the orchestral guise the composer devised in 1859. But he conceived the piece first as a chamber work for flute, two clarinets, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and bass. The original 1858 version, in a reconstruction by Alan Boustead, is the chief fascination on this disc from the New York Chamber Ensemble under Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe. As Clara Schumann suggested to Brahms, the score claimed a symphonic character that seemed to cry out for more instruments. Even so, the chamber version places the music in intimate relief, pointing out the long-breathed lyricism and lilting personality of the pastoral material. Brahms even provided a hint in the orchestral version that he was fond of the smaller incarnation: the Menuetto I and II in the former are scored for flute, two clarinets, bassoon, first violins, violas and cellos. Boustead’s reconstruction may be speculative, but it honours Brahms’s sound world even as it embraces the music’s charm, poetry and moments when the sun slips behind the clouds. The disc’s other novelties are three of Franck’s Pièces brèves, organ miniatures from the last year of the composer’s life orchestrated by Henri Büsser. They are delightful trifles beautifully cast for winds, brasses, strings and percussion. The New York Chamber Ensemble, which made this recording in November 1992, brings ample polish and expressive depth to both scores. The Brahms, from a studio performance, is rendered fresh as motivated by Radcliffe’s judicious tempos and attention to detail and his players’ vibrant interweaving of lines. Donald Rosenberg](https://stephenrogersradcliffe.com/wp-content/uploads/2001/09/Grammophone_Sept_2001-360x1024.jpg)

![Gramophone September 2001 Brahms • Franck [N] Brahms Serenade in D, Op 11 (nonet version, reconstr Boustead) Franck Pièces brèves (arr Büsser) The New York Chamber Ensemble / Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe Roméo Records 7209 (55 minutes: DDD) A fresh, lyrical account of Brahms’s Serenade in its near-to-original chamber version Brahms’s Serenade No 1 in D major, Op 11, is known largely in the orchestral guise the composer devised in 1859. But he conceived the piece first as a chamber work for flute, two clarinets, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and bass. The original 1858 version, in a reconstruction by Alan Boustead, is the chief fascination on this disc from the New York Chamber Ensemble under Stephen Rodgers Radcliffe. As Clara Schumann suggested to Brahms, the score claimed a symphonic character that seemed to cry out for more instruments. Even so, the chamber version places the music in intimate relief, pointing out the long-breathed lyricism and lilting personality of the pastoral material. Brahms even provided a hint in the orchestral version that he was fond of the smaller incarnation: the Menuetto I and II in the former are scored for flute, two clarinets, bassoon, first violins, violas and cellos. Boustead’s reconstruction may be speculative, but it honours Brahms’s sound world even as it embraces the music’s charm, poetry and moments when the sun slips behind the clouds. The disc’s other novelties are three of Franck’s Pièces brèves, organ miniatures from the last year of the composer’s life orchestrated by Henri Büsser. They are delightful trifles beautifully cast for winds, brasses, strings and percussion. The New York Chamber Ensemble, which made this recording in November 1992, brings ample polish and expressive depth to both scores. The Brahms, from a studio performance, is rendered fresh as motivated by Radcliffe’s judicious tempos and attention to detail and his players’ vibrant interweaving of lines. Donald Rosenberg](https://stephenrogersradcliffe.com/wp-content/uploads/2001/09/Grammophone_Sept_2001-scaled.jpg)

![ATHENS DAILY NEWS/ATHENS BANNER-HERALD, Sunday, October 23, 1994 – Page 15A By Ernie Torres Weekend News Editor George Rochberg Rochberg: "Music for the Magic Theater." New World Records. (48:41) ★★★★ The two chamber works on this New World recording by Stephen Rogers Radcliffe and the New York Chamber Ensemble offer an interesting look at George Rochberg's singular brand of modernism. It's not music for the unadventurous, but it's by no means inaccessible. Taking its name from the Magic Theater in "Steppenwolf," the Hermann Hesse novel, "Music for the Magic Theater" is a sound collage of sorts from 1965 in which Rochberg reexamines the music of the past and the present. Over the course of three "acts" there are musical quotations from Mozart's K. 287 Divertimento; Beethoven's Op. 130 String Quartet; Mahler's Ninth Symphony; Webern; Varese; Stockhausen; Miles Davis' "Stella by Starlight"; and Rochberg's own Second String Quartet. Act 1 juxtaposes Mozart with austere and dissonant modernism; Act 2 is mostly Mozart, Miles and melodic; Act 3 is a return to our century's tonal austerity, with a searching, ambiguous and quiet ending. "Music for the Magic Theater" is scored for a 15-piece chamber ensemble. Also on this disc is Rochberg's Octet: A Grand Fantasia from 1980, which is scored for flute, clarinet, horn, violin, viola, cello, bass and piano. Consisting of 12 short sections, the Octet gets off to a fast and gruff beginning but gives way to mostly slow and medium-slow tem- [text cuts off] [Photo Caption] ROCHBERG](https://stephenrogersradcliffe.com/wp-content/uploads/1994/10/Athens_Daily_News_Oct_1994-scaled.jpg)

![ATHENS DAILY NEWS/ATHENS BANNER-HERALD, Sunday, October 23, 1994 – Page 15A By Ernie Torres Weekend News Editor George Rochberg Rochberg: "Music for the Magic Theater." New World Records. (48:41) ★★★★ The two chamber works on this New World recording by Stephen Rogers Radcliffe and the New York Chamber Ensemble offer an interesting look at George Rochberg's singular brand of modernism. It's not music for the unadventurous, but it's by no means inaccessible. Taking its name from the Magic Theater in "Steppenwolf," the Hermann Hesse novel, "Music for the Magic Theater" is a sound collage of sorts from 1965 in which Rochberg reexamines the music of the past and the present. Over the course of three "acts" there are musical quotations from Mozart's K. 287 Divertimento; Beethoven's Op. 130 String Quartet; Mahler's Ninth Symphony; Webern; Varese; Stockhausen; Miles Davis' "Stella by Starlight"; and Rochberg's own Second String Quartet. Act 1 juxtaposes Mozart with austere and dissonant modernism; Act 2 is mostly Mozart, Miles and melodic; Act 3 is a return to our century's tonal austerity, with a searching, ambiguous and quiet ending. "Music for the Magic Theater" is scored for a 15-piece chamber ensemble. Also on this disc is Rochberg's Octet: A Grand Fantasia from 1980, which is scored for flute, clarinet, horn, violin, viola, cello, bass and piano. Consisting of 12 short sections, the Octet gets off to a fast and gruff beginning but gives way to mostly slow and medium-slow tem- [text cuts off] [Photo Caption] ROCHBERG](https://stephenrogersradcliffe.com/wp-content/uploads/1994/10/Athens_Daily_News_Oct_1994-791x1024.jpg)